I’ll confess outright that I love Ken Burns documentaries. I’ve wallowed in Burns’ mammoth definitive overviews of the American Civil War, jazz music, the Old West, the national parks, WWII, and I came very close to the final innings of his mammoth definitive overview of baseball (I started yawning and felt a strong urge for a hot dog and beer, so I missed the last few pitches).

Last year, I read with relish the transcript of his slow-roast of Donald Trump during his commencement address at Stanford University. It was a grand gesture by someone who has strong feelings about America, and it’s not Burns’ fault that the petulant child was elected president. Nobody heeded my words, either.

Burns has been criticized in some quarters for too frequently spotlighting race and racism. While “The Civil War” and “Baseball” can be excluded from these charges, I feel there is also some validity to them, although Burns would argue the spotlight is necessary.

Nevertheless, he’s been called “America’s storyteller,” meaning he has many great stories to tell about America, glorifying this country and its citizens, whether they be black, white, brown, red, or yellow.

Most recently, Burns applied his wizardry (along with co-producer Lynn Novick) to a mammoth definitive overview of the Vietnam War. Considering that this war is still fraught with controversy, this latest documentary series is maybe his most courageous undertaking.

However… like Robert E. Lee at Gettysburg… this time he was unable to secure the high ground.

Why? Unlike the American Civil War, many people from the Vietnam War era are still alive, and some remember things differently. And unlike WWII, America didn’t win, and we weren’t even the good guys. Some American patriots have trouble with that reality, but it’s reality. Burns is at his best when America is at its most noble. But there was little American nobility with Vietnam.

***

Before I discuss why the patented Ken Burns treatment doesn’t work this time, though, I’ll imitate certain mainstream publications (like Rolling Stone, Time, and Cleveland.com) that treat critical American history as if it’s a Steven Spielberg movie:

“Stunning visual achievement!” “Never-before-seen-footage!” “It will make you weep!” “America’s storyteller has done it again!” “A mammoth, definitive overview that will be discussed for years to come!” “Riveting entertainment!” “America is ready to heal, and Ken Burns is the healer!” “A sexy, action-packed adventure!”

(The last two may not be valid).

On surface, I will admit, “The Vietnam War” is breathtaking. Burns and Novick unearthed hundreds of striking images and film bits to pull things along. They present revealing audio of taped conversations from the Johnson and Nixon White Houses that are agonizing to listen to. We know full well the many lies of Richard M. Nixon. But these tapes drive home what a devious, worm-like man he was.

Burns and Novick are also masters at taking a person or persons and creating suspense by slowly fashioning a story for them. One of the most memorable is that of the Crocker family. Each time we see the middle-class house with the front porch and American flag, and hear the peaceful music, we know how the story of Denton “Mogie” Crocker will play out, but we’re addicted to the narrative. We’re voyeurs into how the impressionable Mogie, raised on John Wayne movies and Cold War jingoism, becomes a symbol of young patriotic males everywhere, then ends up dying a grisly death on an anonymous hill in a distant land… for nothing.

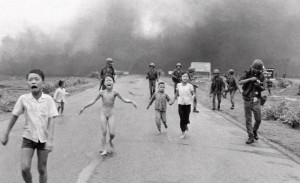

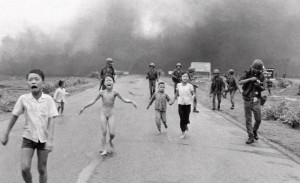

Then there’s the horrific Nick Ut photo of the naked South Vietnamese girl (her name is Phan Thi Kim Phuc) running down the road after being napalmed by a South Vietnamese bomber. Burns takes it a step further and provides a wider landscape. He includes color video footage of the bombing, then people emerging from the fireball, fleeing in terror, with several minutes devoted to the girl, her arms stretched out, the flesh on her back seared.

(Nick Ut/Associated Press)

This rare footage is one of the things Burns is so good at. He stretches the camera frame. He taps our emotions, and we feel the full horror of war through the heart-tugging image of a scarred innocent.

The problem is this: we don’t see the pilot who pressed the buttons that released the napalm bomb. He’s off-camera. Protected.

***

Burns opens his series with his favorite narrator, compelling counterculture statesman Peter Coyote, intoning that the war was “begun in good faith by decent people out of fateful misunderstandings.”

“Decent people” is a subjective term that probably doesn’t belong in a historical documentary, especially when the “people” are surreptitiously leading a nation down the road to war. But no matter.

“Good faith…fateful misunderstandings.” This editorial, at the commencement of the 18-hour presentation, raises significant questions:

Is it good faith that the U.S. funded a French war effort to colonize Vietnam? Then, later, is it good faith that President Johnson, Defense Secretary McNamara, and the U.S. Navy created the fiction of a North Vietnamese attack at the Gulf of Tonkin, to provide a legal basis for Johnson’s escalation of open warfare in North Vietnam?

The only “fateful misunderstanding” was U.S. obsession with a fallacious domino theory of Communism. The rest of our early blunders were the direct consequence of Western arrogance. After France’s hundred-year colonization attempt came to a screeching halt at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, America thought it would be easy to slip in and resume the colonization program. But we didn’t call it colonization, we called it “nation-building” and “winning hearts and minds.” We figured the mighty United States of America could easily subdue a backwater jungle country whose ideological leader was a skinny, sickly Asian.

Ho Chi Minh, speaking in Paris in 1920

The misunderstandings came later. We misunderstood our ability to act as puppeteer to a corrupt and inept South Vietnamese government. And we misunderstood the resolve of the Viet Minh and Viet Cong. This time, they were the patriots and we were the redcoats.

Behind the shiny narrative, here’s the hard reality that Burns and Novick were too coy to discuss:

The U.S. invaded and destroyed another country because that other country wanted a form of government different than the one the U.S. was willing to allow it to have. To prevent that country from exercising the “consent of the governed” that the U.S. deifies as the highest political expression of civilization, the U.S. killed six million Vietnamese, most of them civilians. That is the number from the government of Vietnam. The U.S. spent $168,000 for every enemy combatant it killed. The average Vietnamese earned $80 per year at the time. To carry out this act, the U.S. dropped 14 billion pounds of bombs on Vietnam, three times more than were used by all sides in all theaters of all of World War II combined.

The U.S. carried out industrial-scale chemical warfare on Vietnam, spraying it with 21 million gallons of the carcinogenic defoliant Agent Orange. It destroyed half of the nation’s forests, leaving the greatest man-made environmental catastrophe in the history of the world. When the U.S. destroyed neighboring Cambodia to cover its retreat from Vietnam, the communist Khmer Rouge came to power and carried out the greatest proportional genocide in modern history. The U.S. dropped 270 million cluster bombs on neighboring Laos, 113 bombs for every man, woman, and child in the country. Vietnam had never attacked the U.S., had never tried to attack it, had no desire to attack it, and had no capacity to attack it. All of this was justified through a purposeful campaign of lies to the American people that was sustained by five presidential administrations over more than two decades.

(from www.commondreams.org)

Instead of “begun in good faith by decent people out of fateful misunderstandings,” substitute the above, or similar, as an introduction, and you lay the groundwork for an entirely different documentary. Keep an eye on the reaction of sponsor David H. Koch.

In “The Vietnam War,” Burns presents the micro, but not the macro. He offers numerous anecdotes that imply the war was wrong (big surprise). But we never see just how wrong it was. In the blur of images, interviews, and stories of valor and personal conflict, Burns doesn’t pull his camera back to offer the big picture. There’s sadness and regret, but only a modicum of rage and disgust. We don’t once hear the phrase “war crime.” He plays it safe, struggling to maintain balance and be all things to everyone, left, right, and center. Unless it’s a dead politician, he’s afraid to offend anyone. Including, perhaps, his hefty financial backers.

Burns had ample opportunity (ten years) to make this more than a standard, albeit glittery documentary on a war, and he could’ve lifted it above a stock reiteration of “hate the war, love the warrior.” For example, he profiles Pascal Poolaw, a Kiowa Indian, who fought in WWII, Korea, and died in Vietnam. “The Vietnam War” totally misses the irony of a Native American waging war on indigenous people for a racist, invading nation that, a hundred years earlier, killed and conquered Poolaw’s ancestors in the name of manifest destiny. Instead, we get a brief and awkward puff piece on a minority who earned a lot of medals and died for his country.

There’s an uncomfortable attempt at equivalency, too. “We called them ‘dinks,’ ‘gooks,’ ‘mamasans,’” Coyote ticks off. Then, as if to, again, provide balance, he continues. “They called us ‘invaders,’ and ‘imperialists.’” The first terms are racist and dehumanizing. The last terms are accurate. There’s no equivalency here.

L to R: Secretary of State Dean Rusk, President Lyndon Johnson, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara

And there’s no equivalency between anti-war activists and the so-called “silent majority.” At the end of the documentary, Burns profiles an anti-war activist who breaks into tears and apologizes to vets who were (supposedly) spat on and called baby-killers “and worse.” Yet there is not one bit of video or audio in “The Vietnam War” to substantiate this claim. There hasn’t been any evidence anywhere else, at least, that I’m aware of.

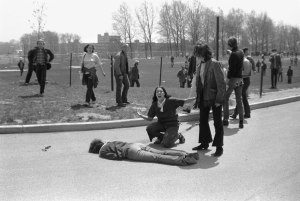

However, there is relentless footage of pro-war Americans screaming at protesters, attacking them, beating them, and berating them as being Commies and traitors… behavior that had its apotheosis in the murders at Kent State by National Guardsmen summoned by Gov. James A. Rhodes of (my home state of) Ohio, who referred to the protesters as “Brownshirts” and “the worst type of people that we harbor in America.”

Where in “The Vietnam War” is the apology from these people?

***

Maybe the biggest question raised by “The Vietnam War” is this: How do Americans want to remember their history? Do we want it to consist of stories of heroism and hubris, triumph and tragedy? Or merely be a series of episodes, a narrative of people, places, dates and events?

Or do we want our history to also inform our present and help determine the course of our future?

Since Vietnam, we’ve continued to send military “advisers” to third world countries, secretly funnel money and arms, initiate coups, topple regimes we dislike, pursue dead-end policies of nation-building, attempt to “win hearts and minds,” wage war under false pretenses, tax Americans to fund war, alienate civilian populations, and label dissenters as being unpatriotic. The only thing we haven’t done is institute a draft.

But there’s no mention of any of the above in “The Vietnam War.” I guess Burns feels it’s OK to offer a static history, as long as it’s dramatic. He’s America’s storyteller, with many great stories to tell.

***

Here are some links related to this article:

The Nation (a liberal publication)

The American Conservative (a conservative publication)

Nick Turse (author of “Kill Anything That Moves: The Real Vietnam”)

Christopher Koch (the first American reporter to visit Vietnam)

You must be logged in to post a comment.