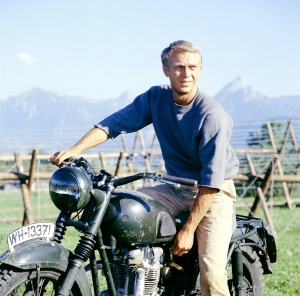

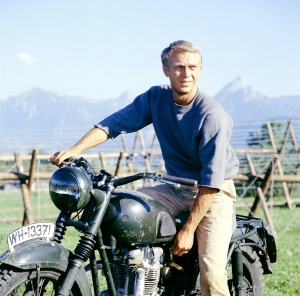

(Tuesday, March 24 is the late Steve McQueen’s 85th birthday. To honor this charismatic actor, here is the second of my two-part commemoration of the man and his films)

There’s a scene in the movie THE GREAT ESCAPE (1963) where American POW Virgil Hilts, known as “The Cooler King” due to his repeated banishments to the isolation box, squats on the dirt in his cramped cell, smiles, and begins to bounce a baseball against the opposite wall. There’s no dialog. But the character’s actions imply “You bastards may be able to kill me. But you can’t eat me.”

This scene is one of many examples of why Steve McQueen earned the title “The King of Cool.”

THE GREAT ESCAPE served notice that a new matinee idol had arrived in Hollywood. As film critic Leonard Maltin observed, “The large international cast is superb, but the standout is McQueen; it’s easy to see why this cemented his status as a superstar.”

After this movie, McQueen was offered one juicy role after another. He was paired with some of the most ravishing starlets in Hollywood: Natalie Wood, Lee Remick, Ann-Margret, Suzanne Pleshette, Faye Dunaway, Jacqueline Bisset. He commanded top dollar for his films. In 1968, his peak year, he starred in two blockbuster films that perfectly exploited his antihero credentials: THE THOMAS CROWN AFFAIR and BULLITT.

Getting passionate with Faye Dunaway in “The Thomas Crown Affair”

In THE THOMAS CROWN AFFAIR, McQueen portrays a wealthy playboy and sportsman who dabbles in high-stakes crime on the side. He’s an ultra-intelligent, smooth operator who enjoys playing chess, riding his dune buggy, reading the Wall Street Journal, and – just for kicks – robbing banks. After masterminding one multi-million-dollar bank heist, an insurance investigator (Faye Dunaway) is hired to trip him up. She comes close to nabbing him in an elaborate game of cat-and-mouse, but of course, she eventually succumbs to his charm. The split-screen scene where McQueen and Dunaway compete in a sexually charged game of chess, then kiss rapturously while the camera whirls around them, is one of the great moments in cinema history, and it assisted Michel Legrand in winning an Oscar for the song “The Windmills of Your Mind.”

Classic photo of McQueen and shoulder holster, from his quintessential film, “Bullitt”

McQueen’s next movie, BULLITT, which was produced by McQueen’s own Solar Productions company, has an even more iconic sequence. The storyline is nothing exceptional: a police lieutenant appropriately named Frank Bullitt (McQueen) is hired to protect a government witness, who is eventually killed, and Bullitt has to contend with both the Mafia and a vengeful politician (Robert Vaughn). But the film is special for its on-location camerawork, the piece-de-resistance being a high-speed car chase across the hills of San Francisco. This 10-minute chase is considered one of the most exciting ever filmed, with veteran racer McQueen doing the close-up driving scenes himself, including a classic spinout in a turbo-charged, 1968 Ford Mustang GT (the high-speed scenes were done by several well-known stunt drivers, one of whom had doubled for McQueen during the motorcycle jump over barbed wire in THE GREAT ESCAPE). During filming, the two cars reached speeds of an astonishing 110 mph. The BULLITT car chase scene became the model for dozens of other similar chases peppered throughout commercials, comedies, and action films. But other than maybe THE FRENCH CONNECTION (1971) starring Gene Hackman, none have come close to McQueen and BULLITT.

After BULLITT, McQueen had enough power and a big enough bank account to race cars and bikes whenever he felt like it. He not only made sure his films had at least one car scene (at least, those set in the automobile age), he also made documentaries about racing, most notably ON ANY SUNDAY (1971), a motorcycle documentary partially produced by and featuring McQueen, and which critic Roger Ebert said “does for motorcycle racing what THE ENDLESS SUMMER did for surfing.”

But McQueen’s film output slowed down considerably after 1969. On the night of August 9, two close friends, actress Sharon Tate and hairdresser Jay Sebring, became victims of the Manson Family murder spree. McQueen had been invited to Tate’s house that same night, but had turned it down because he had a date. He was also supposedly on Manson’s hit list after his production company rejected a Manson screenplay. McQueen’s first wife, Neile, claims that Steve was so spooked he started carrying a concealed handgun everywhere.

Dressed for speed in LE MANS

In 1971, McQueen realized a dream and produced a movie about the renowned 24-hour road race in Le Mans, France. Racing fans love LE MANS for its authenticity – and McQueen never looked “cooler” – but the film plot was fairly opaque, and it was essentially a vanity project for McQueen (he’d turned down the lead role in the earlier racing film, GRAND PRIX (1966), the role eventually going to fellow race enthusiast and friend James Garner).

During the 1970s, McQueen only made five feature films. Two of them, the lighthearted rodeo homage JUNIOR BONNER (1972) and the crime thriller THE GETAWAY (1972), were done with infamous director Sam Peckinpah, who had an affinity for antiheroes and how they cope in a brutal world. In THE GETAWAY, McQueen portrays an ex-con who robs a bank and goes on the lam with his girlfriend (played by Ali McGraw). High on style but low in substance, THE GETAWAY was a much-needed hit for both McQueen and Peckinpah. But it also broke up McQueen’s marriage to Neile, as he and McGraw became lovers during the film, and eventually married (then divorced in 1978).

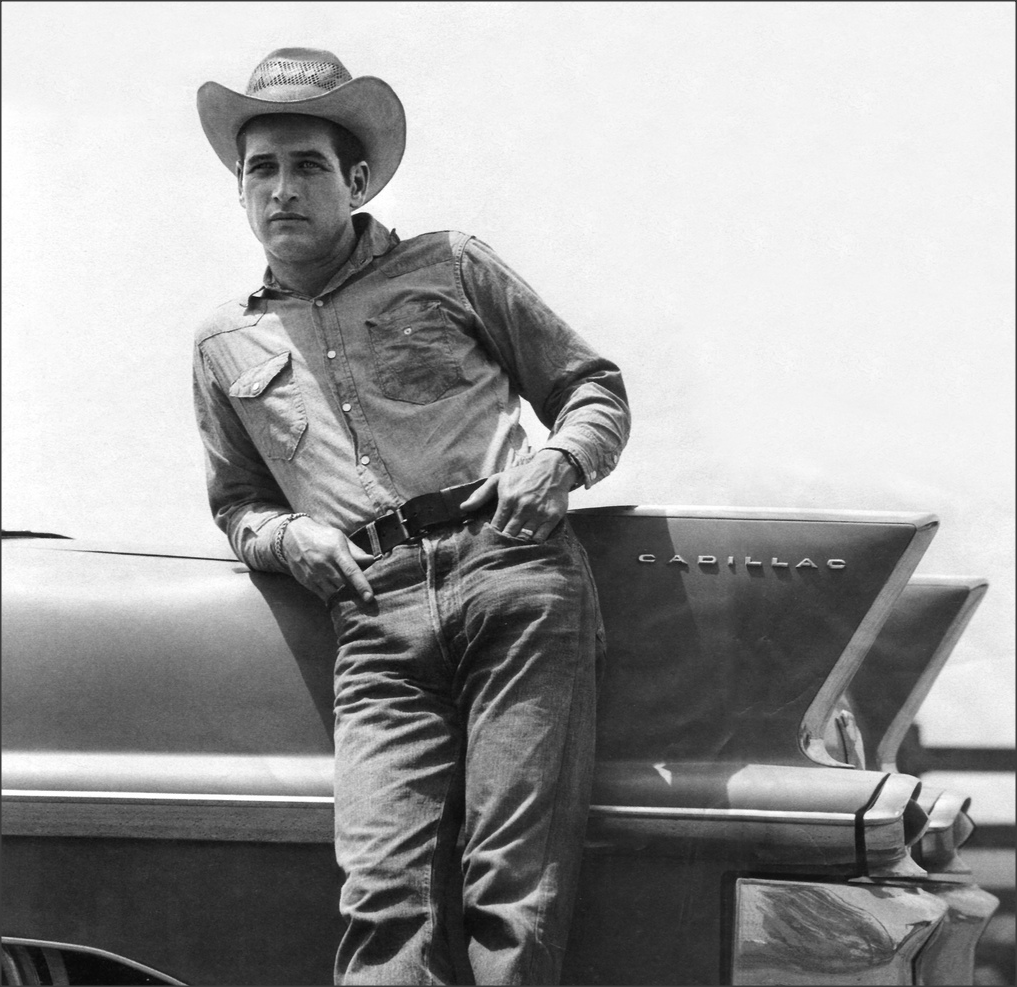

In 1974 McQueen was reunited with Paul Newman, one of the few actors who could compete with him at the box office. They headlined the Irwin Allen disaster epic THE TOWERING INFERNO, with McQueen playing a fire chief, and Newman portraying an architect. Both actors wanted lead billing… but which one would get it? The producers solved the dilemma by putting McQueen’s name first, on the left, but Newman’s name slightly higher, on the right! Additionally, both actors received the same pay and had the same number of lines. Poor William Holden, also in the film, had evidently become too old to compete with the other two!

McQueen’s last film of the ‘70s was another vanity project: AN ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE, based on a Henrik Ibsen play, and in which McQueen played a principled doctor who has a feud with his materialistic neighbors. The McQueen everyone knew and loved was practically hidden behind a beard and spectacles, and the film had an extremely limited theatrical release.

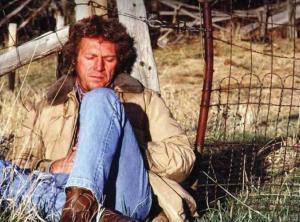

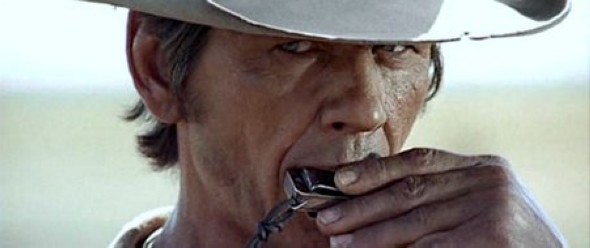

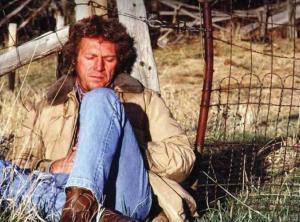

Taking a break on the set of TOM HORN, his second-to-last film

McQueen returned to familiar territory for his last two films, TOM HORN (1980) and THE HUNTER (1980). The former is a period piece based on true-life cowboy bounty hunter Horn, who was controversially hanged for murder in 1903. In THE HUNTER, McQueen played a contemporary bounty hunter, and was reunited with THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN co-star Eli Wallach. Although both movies were up McQueen’s alley (recalling bounty hunter Josh Randall in “Wanted: Dead or Alive”), both were unfortunately critical and commercial disappointments.

It was during the filming of TOM HORN that McQueen started to have trouble breathing. He was eventually diagnosed with malignant mesothelioma, an aggressive type of lung cancer (though McQueen was a heavy smoker, Neile cited the cause as asbestos exposure, possibly received from Steve soaking his racing facemask in the chemical, which was an oft-used fire retardant… it was long before the dangers of asbestos were known). McQueen fought valiantly against his cancer. He even resorted to controversial treatments that involved coffee enemas and injections of live cells from cows and sheep. But on November 7, 1980, after surgery in Juarez, Mexico to remove a massive tumor, he died of cardiac arrest. He was only 50 years old.

Layin’ back with James Coburn in pickup truck. Note the Castrol motor oil and Lucky Lager beer bottles

Since McQueen’s death 35 years ago, he’s been the subject of many biographies. He’s been name-dropped in songs by the Rolling Stones, Leonard Cohen, Jimmy Webb, Sheryl Crow, UFO, and many others. The English band Prefab Sprout named an entire album after him. According to Wikipedia, possessions by the late actor sell in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. He had a collection of 130 motorcycles that sold in the millions within four years of his death. Lines of expensive clothing and watches have been inspired by him. Most tellingly, his estate is in the top 10 of highest earning deceased celebrities. Long after his death, the King of Cool remains a hot property.

And how many actors have been inducted into both the Motorcycle Hall of Fame and the Hall of Great Western Performers?

For a brief moment in the ‘60s and ‘70s, a rugged, blue-eyed ex-reform school punk named Steve McQueen burned like red lava flowing from an active volcano. Even in ensemble films, McQueen was so magnetic a presence you couldn’t tear your eyes away from him. If you were born too late to catch him the first time around, his films are still easily available. Below is a short list of what I consider his best flicks (I’ve already discussed three of them). So grab some popcorn, turn down the lights, and enjoy a Great Escape with the King of Cool.

1. THE GREAT ESCAPE (1963)

2. NEVADA SMITH (1966). Based on a character in Harold Robbins’ novel “The Carpetbaggers,” this is a compelling Western about revenge. McQueen plays a half-Indian teenager (you heard right) whose parents are brutally murdered by three outlaws. One by one he tracks them down. McQueen gets to display his athleticism in some great action scenes, including a tense knife fight with his former Actors Studio buddy, Martin Landau. The final scene with Karl Malden is killer.

3. THE SAND PEBBLES (1966). McQueen was nominated for four Golden Globe awards during his career, but this was his only Academy Award nomination.  He plays a rebellious, Brooklyn-bred machinist’s mate stationed on a Yangtze River gunboat in 1926. He’s not only convincing in his role, but the film has a great supporting cast, including Candice Bergen, Richard Attenborough, and Richard Crenna.

He plays a rebellious, Brooklyn-bred machinist’s mate stationed on a Yangtze River gunboat in 1926. He’s not only convincing in his role, but the film has a great supporting cast, including Candice Bergen, Richard Attenborough, and Richard Crenna.

4. THE THOMAS CROWN AFFAIR (1968)

5. BULLITT (1968)

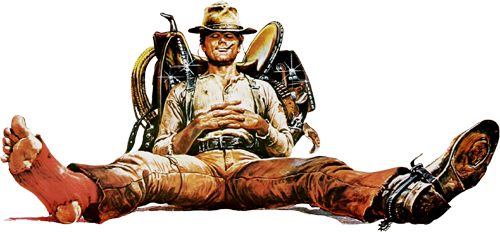

6. THE REIVERS (1969). One of the best all-round movies McQueen made, THE REIVERS is based on a lesser known novel by William Faulkner. It’s a totally winning slice of rural Americana, with McQueen stepping out of his comfort zone and playing Boon Hoggenbeck, a conniving roustabout who cons a young boy into “borrowing” his grandfather’s 1905 Winton Flyer automobile for a trip down the backroads of Mississippi.  The film comes a little close to Disney territory, but there’s enough sobriety to keep it honest, and McQueen never looked happier. And this time he gets to goof in the mud with an antique set of wheels!

The film comes a little close to Disney territory, but there’s enough sobriety to keep it honest, and McQueen never looked happier. And this time he gets to goof in the mud with an antique set of wheels!

7. PAPILLON (1973). McQueen shares the spotlight with another Hollywood legend, Dustin Hoffman, in this tale (based on a true story) about two Frenchmen who are exiled for life to Devil’s Island prison off of French Guiana in the 1930s. No need to worry about Hoffman, though: McQueen is the whole movie. This film is full-fledged action-adventure, and it’s both long and intense. It deals with the indomitability of the human spirit (think of it as THE GREAT ESCAPE on acid). Like so many McQueen films, this one features several classic scenes: a skillfully photographed slow-motion sequence of McQueen stumbling into a jungle river while trying to escape; and the final shot, when he catapults himself off a massive cliff into the ocean. Characteristically, McQueen insisted on doing this dangerous stunt himself. The King of Cool got his way.

He plays a lazy, happy-go-lucky cowboy who teams with his brooding brother to protect a town of pacifist Mormons from a ruthless land baron. Lighthearted fare with lots of funny moments (including hilarious overdubs).

He plays a lazy, happy-go-lucky cowboy who teams with his brooding brother to protect a town of pacifist Mormons from a ruthless land baron. Lighthearted fare with lots of funny moments (including hilarious overdubs). I haven’t seen it in years, but I remember it as a minor gem with lots of atmosphere. A highlight is a great arm wrestling scene with live scorpions on the table. Unrelated to

I haven’t seen it in years, but I remember it as a minor gem with lots of atmosphere. A highlight is a great arm wrestling scene with live scorpions on the table. Unrelated to

It stars

It stars  Another Brando flick, this was his only directorial attempt and is maybe the first Revisionist Western. He plays Rio, a robber who is double-crossed by his older partner, Dad Longworth (

Another Brando flick, this was his only directorial attempt and is maybe the first Revisionist Western. He plays Rio, a robber who is double-crossed by his older partner, Dad Longworth ( Fonda is chilling as the villain, Bronson is moody and mysterious, and Robards adds class.

Fonda is chilling as the villain, Bronson is moody and mysterious, and Robards adds class.

He meets an eccentric grizzly hunter, is forced into leading a group of pioneers through hostile Crow country, and soon has to defend himself from isolated attacks by Crow warriors. Atmospheric, with sparse dialog, it is (literally) great escapism.

He meets an eccentric grizzly hunter, is forced into leading a group of pioneers through hostile Crow country, and soon has to defend himself from isolated attacks by Crow warriors. Atmospheric, with sparse dialog, it is (literally) great escapism. This movie is perfect on every level. It is tragic, funny, dramatic, has great acting (

This movie is perfect on every level. It is tragic, funny, dramatic, has great acting ( Sergio Leone, Clint Eastwood, Eli Wallach, Lee Van Cleef, soundtrack composer

Sergio Leone, Clint Eastwood, Eli Wallach, Lee Van Cleef, soundtrack composer

You must be logged in to post a comment.